For a great-grandmother who lived 3500 km away, I knew her pretty well. After all, I was 20-years-old when she passed away at the age of 102.

We visited her every summer growing up. Nous parlions en français, lentement, avec mesure, and with a sing-songy tune because she knew no other way to speak, and it was utterly infectious. She was forever upbeat, always a shining beacon of positivity. She always had news to share about the frontiers of technology, space exploration, efforts for peace in Israel, and more seemingly fanciful curiousities. Despite being nearly blind in her later years, she dutifully read National Geographic and other periodicals letter-by-letter, cover-to-cover, using a CNIB reading machine that looked like a 1950’s TV. She loved showing off her morning routines to guests, a routine that included air kicks, air punches, stretches, and counting to twenty in twenty different languages.

Although she passed away peacefully in 2006, she’s been on my mind lately. Not just because it was her yahrzeit this week, though it was, but because I can’t think of a more aspirational figure for The Girl. As My Love prepares to take her first sabbatical – the first meaningful break from the grind of a decade-plus of professional practice, motherhood, and tolerating yours truly – I desperately want to avoid the societal default of her feeling like a “kept woman.” I don’t want her to be trapped; I want her to feel as free and empowered as I do, and as Mamaia did.

Although she passed away peacefully in 2006, she’s been on my mind lately. Not just because it was her yahrzeit this week, though it was, but because I can’t think of a more aspirational figure for The Girl. As My Love prepares to take her first sabbatical – the first meaningful break from the grind of a decade-plus of professional practice, motherhood, and tolerating yours truly – I desperately want to avoid the societal default of her feeling like a “kept woman.” I don’t want her to be trapped; I want her to feel as free and empowered as I do, and as Mamaia did.

So what was Mamaia’s life really like? And what can we learn from it? While I don’t know all the pieces to the puzzle and I still have more research to do, here’s what I know so far: born in 1904 to a reasonably affluent family, Mamaia went to grade school at the local convent in Bucovina,i where girls from literate minority families of several backgrounds sent their daughters to be educated. Mamaia then married well, to a good Jewish boy in the business of ceramic tile manufacturing, after which she was treated to a life of fine arts, literature, languages, and self-directed freedom. Supported by a full staff, she entertained when she pleased, attended to their two boys when she pleased, travelled when she pleased, and generally did as she pleased. She was a free woman, one who’d earned her freedom by marriage, which had been in turn earned by her beauty, charm, and sophistication. She lived a priviledged life in Cernovitsi, a cosmopolitan hub referred to variously at the time as “Little Vienna” or “Jerusalem upon the Prut.” She lived a life defined by freedom, curiousity, and optimism.

Even when all of her material comforts were stolen from her and her family in the late 1930’s, she never looked back. She never let herself be defeated by the past. Although she suffered hardship and persecution during the war and in the difficult decades to follow, she always looked forward… onwards… upwards! She saw hope amidst the chaos; life amidst the death.ii

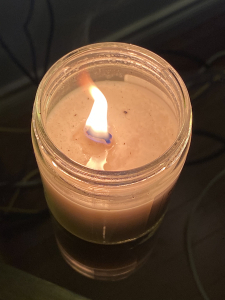

Somehow, someway, she saw a bright future for humanity and for her family as well. In places full of smart, hard-working immigrants like Israel, the United States, and Canada, she saw opportunity for a better tomorrow. That was the Mamaia I knew. C’est la chandelle dont je me souviens. That’s the kind of woman the world need more of today…

The one I aspire to provide it.

___ ___ ___

- Not unlike Zaha Hadid in a slightly different time and place, viz. Iran in the 1950’s and 1960’s. ↩

- If anyone ever lived by the phrase “l’chaim,” it was my great-grandmother.

What is l’chaim? I’m glad you asked, Little Timmy. Here are a couple of quotes from seminal Contravex articles you may not have read yet:

It’s irrefutable that sexuality is defined by the penetrator and the penetrated as the fundament of any sexuate species, and yet before Judaism none had thought to make this about “gender.” Why ? Because l’chaim, that’s why. This is ironically a denial of biology, which demands that the fringes be explored without regard for the wellbeing or even continuance of the individual, but that’s the Jewish pathos for you. Even the Jews know that the fringes don’t always hit their marks – often times they’ll miss horribly and lose their lives for their troubles – but the dynamic is what’s important. The agency goes to the active because the penetrator takes the risk for the reward. Maybe he fucks an electrical socket. But maybe he fucks Cleopatra. That’s the chance he takes. Yet Judaism, and subsequently Christianity, attempted to corral this experimentation with the institution of (largely monogamous and definitely heterosexual) marriage. The idea being, I suppose, that sexual energies would then be directed towards commercial ends and experimentation in that arena and that arena alone, which would then better serve the group than would the pursuit of strictly biological ends. This is only too true in the cities we find swelling the world over today, but it was a less than ideal strategy in pre-industrial agricultural societies. I guess it’s a good time to be alive!

via Urbanism feminises, Judaism desexualises. Or the waxing fashionability of being penetrated.

It’s quite the stereotypically Jewish moment really. Life is always worth living. Life is always worth preserving. Life is everything. To life! Not to health, do Jews toast one another, but to life. L’chaim!

~ To life, to life, l’chaim! L’chaim, l’chaim, to life! ~

L’chaim. Not sante. Not salud. Not to prosperity or benefit or joy or anything like that. But to life.